A Utility's Renewable Energy Generation Problem

Why Duke Energy is selling off renewable sources of energy even as it approaches reducing carbon emissions and retiring coal-fired power plants

In June 2023, Duke Energy announced the sale of its unregulated commercial renewables business to Brookfield Renewable, making about $1.1B on the deal. With that sale expected to close later this year, what does this mean for the utility’s plan to reduce carbon emissions by more than 50% by 2030 and retire all of its coal plants by 2035? Well, probably nothing. That’s because as an investor-owned utility, Duke Energy had no other choice to keep investors happy. Let’s dive in.

Investor-owned Utilities Need Big Projects

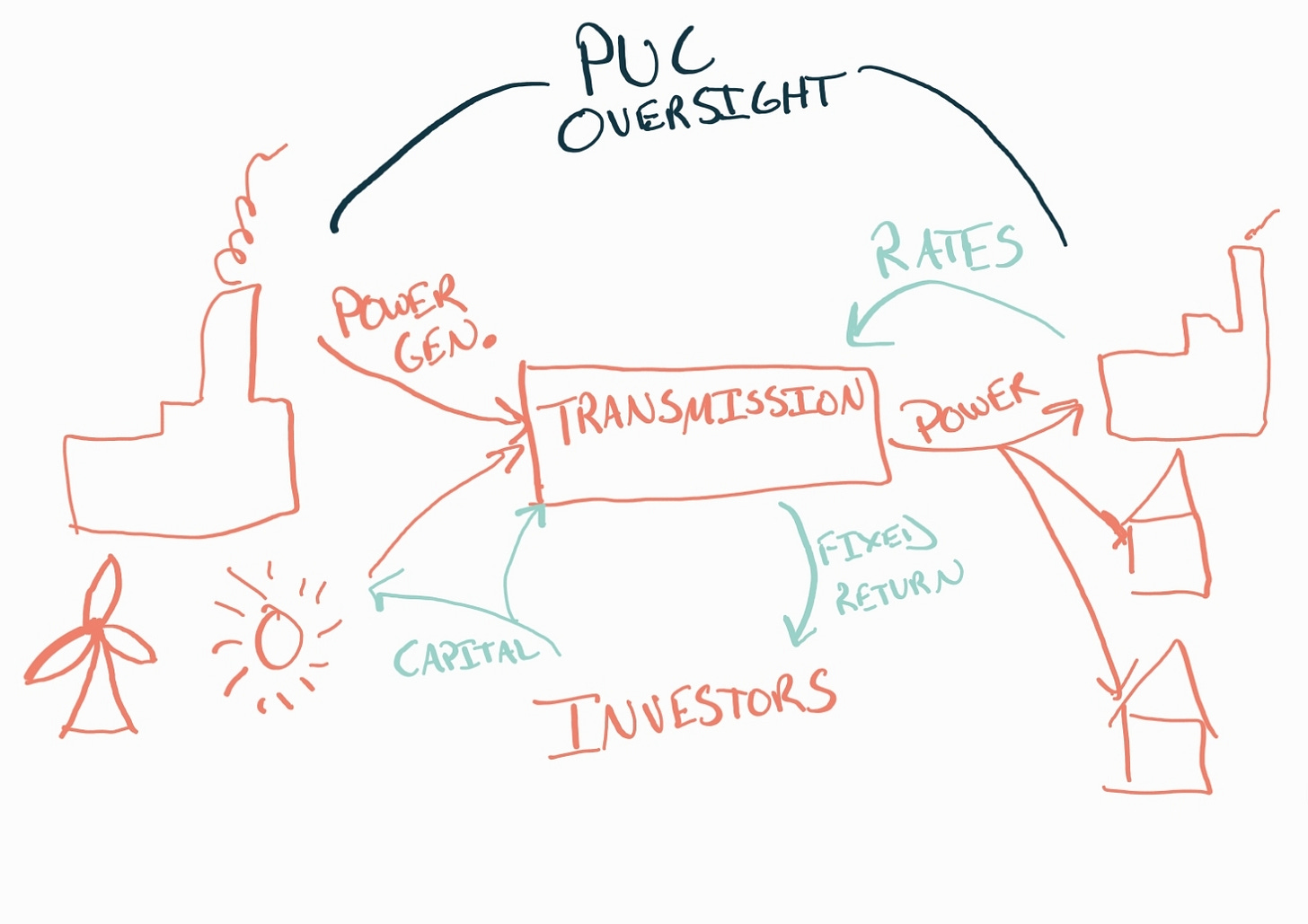

Investor-owned electric utilities are usually regional monopolies that are regulated by the government to provide stability and standardization to the electric grid. They came around near the beginning of the 20th century as demand for electricity in homes and businesses started to skyrocket. The infrastructure needed to be built out quickly, and it wasn’t ever going to be efficient to have multiple businesses laying down power lines and building power plants that compete with each other. However, the United States in particular, had just come off of a regulatory disaster with railroads and there was public distrust in allowing a monopoly to form. Hence, the Public Utility Commission (PUC) was born! Electric utilities could operate as natural monopolies but many of their decisions that directly impact consumer welfare such as rate setting would require approval by the government-appointed PUC. A century later, we have electric utilities that are some of the largest businesses in the United States (e.g., Duke Energy is a Fortune 150 company), and their structure of making money is highly scrutinized by regulators.

The system has worked reasonably well since its inception. Nearly everyone gets electricity who wants it and when the investor-owned electric utility isn’t treating consumers as they would like, the public has levers to pull as we are currently seeing in Maine with the Pine Tree Power ballot initiative to dissolve investor-owned utilities in Maine and convert them to a fully government-owned entity.

This level of regulation has become ingrained in the business model for utilities like Duke Energy:

Investors provide capital, the utility proposes projects to the PUC with allowance for a fixed return on the invested capital, then projects get built and everyone gets to make some money while rates stay relatively constant as they provide mostly operating capital. Over time, this has made investing in utilities a favorite cash flow investment, particularly in the past few decades of ever falling interest rates that pummeled the traditional bond market.

However, it’s risky to rely on approval from a government body to keep investors happy. Appointments can change, public sentiment can flip, and the process can be downright slow. That means going to get approval as infrequently as possible is the best recipe for success and that means big projects. This is absolutely reflected in the latest version of Duke Energy’s $65B carbon plan that has been seeking approval since May 2022 when it was first submitted. This is an “all of the above” strategy in which emissions are reduced via moves to renewables, nuclear, and lower emitting sources such as natural gas. Bundling everything together with projections of growth in demand and getting a one time approval is how to keep the investors getting back their expected returns while mitigating political risk factors.

Built Renewable Capacity as a Liability

It’s difficult and risky to get new projects approved but why sell what has already been built? First, consider the buyer. Brookfield Renewable focuses on power generation using renewable sources and sells the electricity it generates to the utilities who then distribute that to end users. This means Brookfield doesn’t really have a relationship directly with consumers and thus less regulatory scrutiny. If the power is online and meeting the contract, they get paid. Otherwise, Brookfield doesn’t get paid and the would-be purchaser has to figure out how to fill in the capacity some other way.

To Duke Energy, these already-built, utility-scale had become a liability. If something went wrong, they needed to fill in the capacity anyway, and without the focused expertise on solar, it didn’t make sense to continue to hold the assets. Purchasing long term, inflation linked contracts for the power from Brookfield reduces the operational burden for Duke Energy now that they’ve already gotten the return on the installation of the projects. Duke Energy's model for renewables, at least right now, seems to be to build generation capacity, hold until the fixed return it generates for investors is over, then spin it out to reduce liability. This is a new strategy considering the number of power plants otherwise under operation by Duke Energy.

Decentralized Generation and Transmission Utilities

Duke Energy, like many other electric utilities, owns both generation and transmission of electricity within its market. However, I think it is fair to wonder how this evolves. Land use of solar farms is inefficient, particularly in areas that are not deserts. Rooftop solar is a more efficient land use pattern for solar, but these projects are small in capacity and large in number, so it seems unlikely an investor-owned utility would ever become interested in making this a common pattern unless they were forced to by regulation.

What happens if that regulation never comes to force utility support for rooftop solar? I don’t think it’s necessarily a problem so long as installation by individuals isn’t artificially limited. Batteries are getting cheaper and electric vehicle adoption is on the rise, providing a large capacity battery that sits at home often during times that solar is not generating. Currently, Duke Energy’s model for electricity demand going forward considers huge increases in load due to EV adoption and population growth. That demand is on the generation side, but the money made on generation projects feeds investment in transmission today. I suspect the leading indicator of trouble for investor-owned utilities is if they start to spin off their long held generation capacity to other players to focus on transmission only. I’m watching this area because this isn’t the first move in this direction. Back in 2018, Duke Energy sold off hydroelectric capacity that had become too expensive to operate. Maybe in a world of decentralized generation, this is how it should play out anyway. After all, the natural monopoly today is only transmission – anyone can put up solar panels and make electricity now. A bit more than a century into the game, consumers and businesses are starting to get a choice in how their electricity is generated and that’s good for the market.