A quick follow up on last week’s post on thin film solar. There’s so much more to dig into with the future of thin film solar itself as a technology. I do think it’s an uphill climb for it to displace gains made by silicon modules worldwide. First Solar’s government backing in the United States gives it a chance to make thin film solar a major player, but I wouldn’t bet big on it until we start seeing at scale deployments of canal solar or roof shingle solar. I should’ve communicated that as the point more clearly, so thanks for the feedback!

This week I’m talking about the ramifications of passively collecting abundantly available energy rather than digging up hard to find fuel. This new paradigm creates new economic opportunities. These opportunities are currently available where transmission is expensive to build or consumption is highly predictable and concentrated. Suburban housing, cell towers, and strip malls are three areas to expect to have a much different look over the next decade.

Passive vs. active collection

Renewables combined are expected to become the world's majority power source by 2030, with wind and solar dominating. That means a fundamental shift in how we think about energy collection. Solar is a passive collection of abundant energy radiated to earth. Wind is also a passive collection but has a stronger geographic dependence and relatively higher capital investment to build out. Challenges with distribution and storage are clear given there’s been more than a century of digging up fuel and burning it centrally. That model has led to assumptions that I believe will begin breaking down over the next several years in conditions where transmission is hard to build or energy usage is high enough to warrant a medium sized capital expenditure.

The question is how do we capture the energy we need that is being thrown at us all the time and make it productive? I think this would fundamentally change how we think across many different industries, but I want to focus on three for now: suburban single family housing, data transmission networks, and grocery retail.

Power to the people

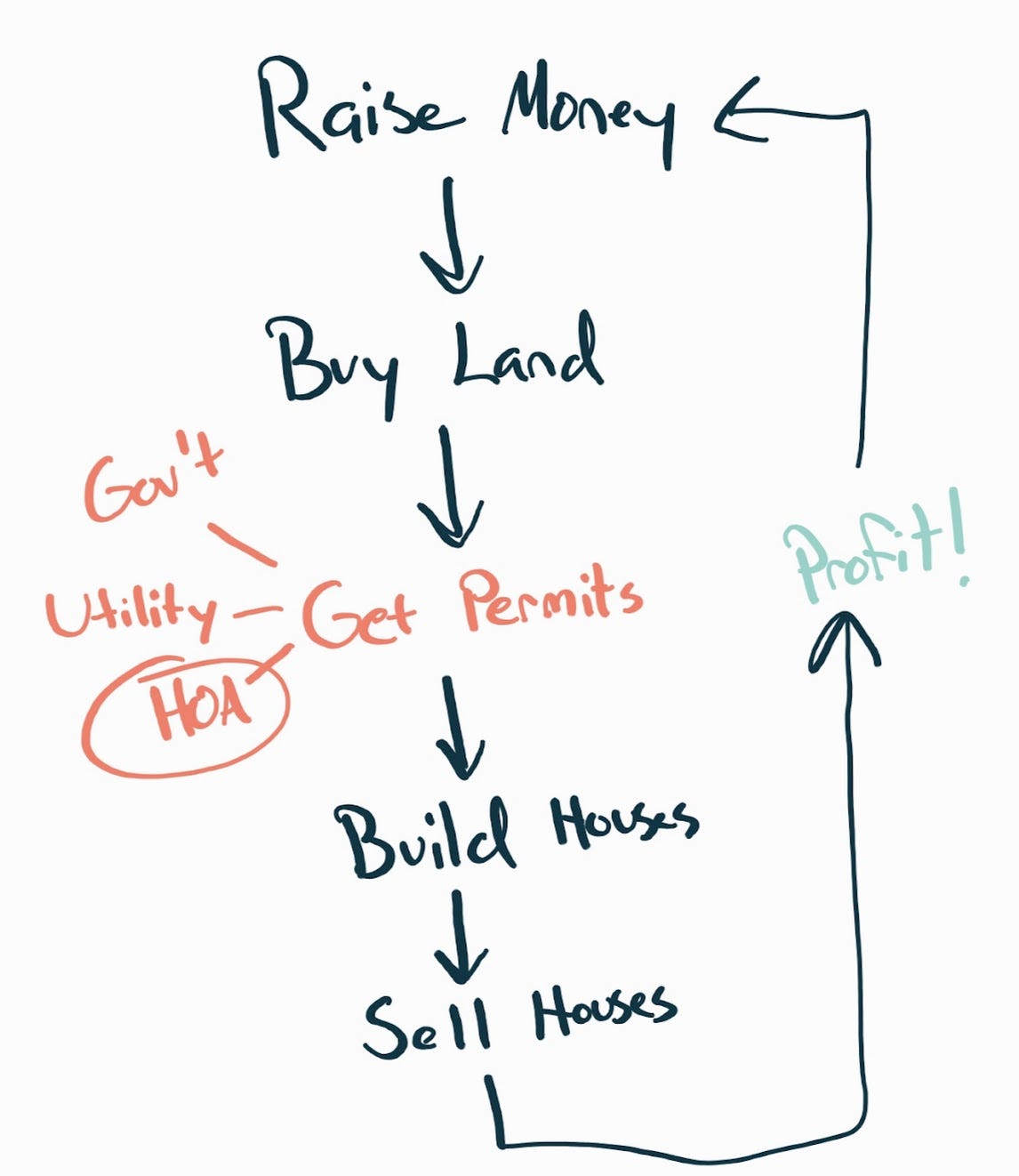

Most suburban single-family housing is built by real estate developers who have collected money from investors, purchased land and building materials, and gone through all of the necessary regulatory bodies to be allowed to build housing.

A simplified view of the business model is to get the housing sold at a premium as quickly as possible so they can recover costs, return money to investors, and move to the next project where they can raise more capital. The holding cost of the land and building materials prevents them from moving to new projects, so avoiding delays due to government approvals is a major factor. Secondarily, developers want to keep the housing attractive until all units are sold. A homeowner association (HOA) is a common way to handle this from both angles. There’s a long, complicated history of HOAs in the United States but the net-net of it for this discussion is developers promise to take care of stormwater, landscaping, and other services usually rendered by a local municipality to avoid getting bogged down in local government politics. Providing electricity could become an HOA managed service with a small leap ahead of what co-ops do today. Newly built suburban and even rural communities of single family dwellings could have rooftop solar and local batteries powering each home and it wouldn’t cost the developer much extra to make it happen and would be lucrative as a differentiator for new developmentsDownstream impacts on appliances and home layouts are knock-on opportunities for what has been a niche industry of off-grid HVAC units that work well with DC electricity. I’d expect multiple smaller units designed with DC in mind that are controlled by a more elaborate system of sensors and thermostats than we see today to orchestrate amongst the units. There’s no technological barrier to this opportunity today, only inertia.

Cell towers make new communities

Data centers are huge energy consumers, accounting for about 1% of all electricity consumption in the world today. Surprisingly (at least to me), data transmission networks use about the same amount of electricity as data centers when excluding crypto mining from data center power consumption. While you can co-locate a data center with a more traditional centralized energy source (e.g. nuclear power plant, hydropower plant), this just isn’t possible when looking at the decentralized mobile networks that exist around the globe. Coverage is king and that means finding power in a wide variety of settings. GSMA is already asking for policy updates including grid updates because:

Where there are outages operators must rely on alternative sources of energy, either diesel generator solutions, with associated carbon emissions or very local solar/wind solution that are less cost efficient due to lack of scale compared to large scale renewable electricity supplied through national grids.

While urban areas probably don’t change much given the small deployment footprint of 5G small cell networks and the need to keep them close together, the more spread out rural deployments would benefit from a decentralized energy network. As GSMA suggests, more collaboration between public and private sectors here would result in more energy capture and the potential for communities to spring up around where rural towers are located. In developing countries, this would provide a boon for both electricity and communications buildout. To date, companies building out these networks have focused on providing money to fund Virtual Power Plant initiatives, but a continued drop in energy storage prices would make it appetizing for them to get into the game themselves.

Selling food and electricity

Retail grocery stores in the United States are in a notoriously tough business fraught with low margins, difficult inventory challenges, and high expectations from their communities to anchor strip malls. Energy Star estimates electricity and natural gas bills for these stores are around $4/sqft. With a typical store being 50,000 sqft. That's a large bill eating into the bottom line. It would be a large capital expense to build out a solar and storage system to power a grocery store, but the real estate between the roof and parking lot is abundant. Often these stores are the anchor tenants in strip malls, so it’s also reasonable to expect the store could become a power supplier for surrounding businesses and potentially collect a bit more upside on the investment. Major grocers Walmart and Target are already in the top 10 of deployed rooftop solar nationwide, and they aren’t doing it altruistically. I expect other major grocery chains across the country will follow suit. The Kroger/Albertsons tier would be more likely to push for collecting energy payments from the other strip mall tenants whom they anchor to drive faster payback on the capital expense as Walmart and Target are more often deployed as standalone stores.

I think it’s a great time to own a high energy consumption business if you have a decade-long time horizon in mind. Similarly, as I mentioned in A Utility’s Renewable Energy Generation Problem, it’s going to be a tough time to be an investor-owned utility. I expect there will be lobbying and regulatory pushback to prevent further grid decentralization, but the economics are already starting to tilt in favor of decentralization in cases with low population density or high consumption businesses.